Steps Must Be Taken to Increase Viewpoint Diversity Among the University Faculty

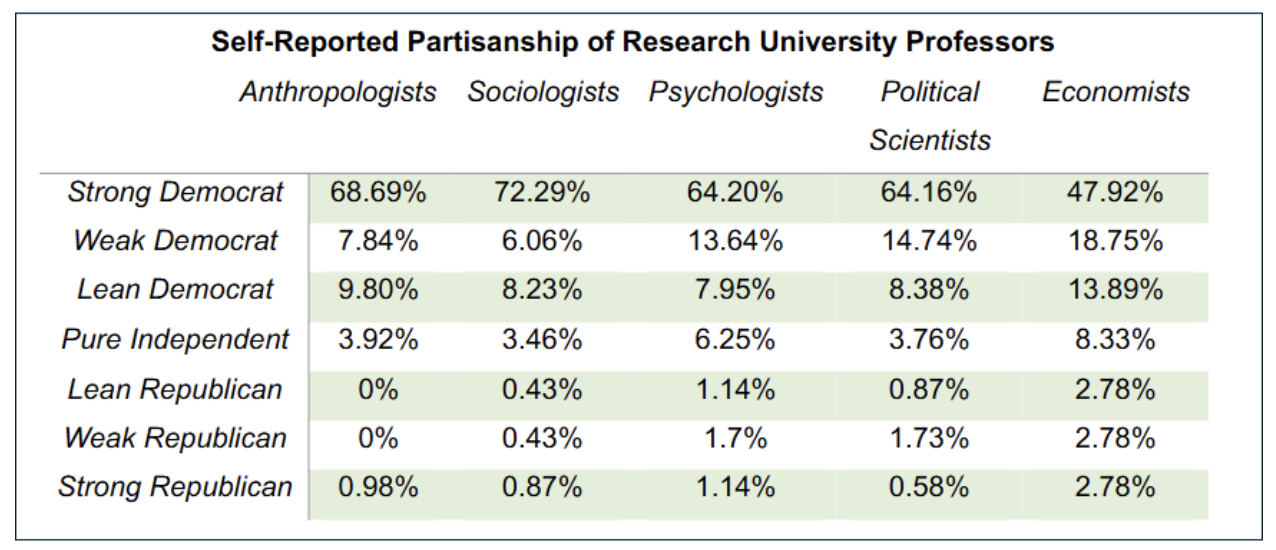

Recent surveys have shown that university faculties, especially in the humanities and social sciences, have increasingly tilted to the left in recent years. For instance, a 2020 survey by Joshua Koss, a political scientist at Michigan State University, of tenure-track faculty across 67 universities that are members of the American Association of Universities revealed a striking partisan imbalance across the main social science disciplines, shown in the table below:

While we do not have specific data for the University of Washington, it is reasonable to assume that its faculty tracks closely with this distribution. And while university faculties have long leaned to the left, this overwhelmingly lopsided distribution is a more recent phenomenon. See https://ctse.aei.org/partisan-professors/.

Writing in 2017, Samuel Abrams succinctly described the damage that this skewed distribution does to higher education:

“When almost everyone in a field or department shares the same political orientation, certain ideas become orthodoxy, dissent is discouraged, errors can go unchallenged, and these orthodoxies inhibit scholarly inquiry. Groups of scholars whose worldviews are in broad agreement are more prone to confirmation bias and less likely to challenge scholarship that comports with their views.

This ideological narrowing is dangerous not just for the creation of new knowledge and research, but also because it does a disservice to the very people we professors are trying to educate and lift upward. Ideological homophily all but assures that students will go out into the world less able to see the world as it really is, and poorly equipped to defend their worldview. As teachers, we fail in teaching students how to think. When students are shielded to divergent view points and counter-arguments on the issues that are more salient to them, the students understandably become confused and angered by others who see the world differently. This diminishes our national discourse and frays our civic bonds.” https://www.the-american-interest.com/2017/03/10/mind-the-professors/

The actual and perceived political bias of faculty also leads to a loss of public confidence in academia, which has wide-ranging negative impacts, not just on universities, but also on science, policy, and society at large. If the public doubts academic institutions, research findings may be dismissed as biased, ideological, or irrelevant, weakening public confidence in the academy’s policy inputs on critical issues, from climate change, to public health, to basic scientific research. Without trusted experts, society struggles to agree on facts, making it harder to solve collective problems (pandemics, climate change, AI governance). The loss of public confidence doesn’t just hurt universities; it undermines the whole system of knowledge-based decision-making that modern societies rely on.

In short, viewpoint diversity is essential for preserving the prestige of academia and its important role in promoting sound public policy.